By: Brian J. Meli

It’s that most wonderful time of the year again, when kids are jingle belling and everyone’s telling you to be of good cheer. And sure, they’ll be parties for hosting and much mistletoeing, but they’ll be some grousing too—and not just over having to allow eccentric relatives access to your home and hearth. This kind of complaining has to do with the perception, right or wrong, that the true meaning of Christmas is getting buried beneath all the glitz, glamor and excess of the modern holiday season. For more on this topic, look no further than the latest scandal to rock the White House.

Arguments over the traditional theological and modern secular versions of Christmas have raged for a long time. But no matter how you view this hap-happiest time of the year, there really isn’t much debate that, for better or worse, the imagery that’s come to define the contemporary Christmas experience is derived as much from the formidable capitalist forces of mid-20th century America as it is from anything existing at the time of the birth of Christ.

Three of the most famous characters associated with Christmas, after all, have their roots in modern American consumer culture. Two of the three were actually conceived by Madison Avenue pitchmen. And when characters get created to shill products, even ones that have become beloved Christmas icons, it raises all sorts of trademark, copyright and other intellectual property issues. So before you fill up the stockings and deck the halls this year, let’s take a moment to consider who actually owns the properties we traditionally associate with Christmas.

1. Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer

Laugh and call him all the names you want, but in addition to delighting starry-eyed children for over half a century, Santa’s ninth reindeer has some serious licensing power behind him. Rudolph can trace his lineage to a poem written in the 1930s by an advertising copywriter named Robert May, who was commissioned by Montgomery Ward to contribute to a brochure distributed to store shoppers during the holidays. (A very early example of successful content marketing.)

1964’s Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer

The poem about the deer with the shiny nose was such a big hit that ten years later, May’s brother-in-law, a radio producer named Johnny Marks, adapted it into the song that became forever immortalized by Gene Autry in 1949.

The copyright in that song is the property of St. Nicholas Music Inc., the company founded by the late Marks, which also incidentally holds the rights to other holiday classics like “A Holly Jolly Christmas” and “Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree.”

But as far as Rudolph himself is concerned, the misfit reindeer has his own chain of title, and it’s a rather unique one. Unique because the custom back then, as it is now, was for work created by copywriters on behalf of advertisers to be considered works-made-for-hire, and therefore the property of their employer from the moment of creation. Not so with Rudolph, however. As history tells it, the then President of Montgomery Ward, in an act of goodwill befitting the Christmas spirit, allowed Robert May to keep the rights in the character he created, even though he knew it had value.

Those rights eventually passed to May’s company, The Rudolph Company L.P., which licenses the copyright and trademark rights in Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer to this day. So the next time you put a blinking Rudolph on your front lawn, or pop that Rudolph Christmas special into the DVD player, you can take comfort in knowing you’re helping support the family of the man who actually created him.

2. Frosty the Snowman

While the legend of Frosty the Snowman may be a heartwarming tale of love and loss, Frosty doesn’t in fact belong to children’s imaginations at all, but to two of America’s largest media conglomerates.

1969’s Frosty the Snowman

Frosty came to life one day in 1950, not from an old silk hat, but through the creative talents of two songwriters, Jack Rollins and Steve Nelson, who set out to create a follow-up hit to the hugely popular “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” released a year earlier. As with Rudolph, Gene Autry originally recorded “Frosty the Snowman.” And as with Rudolph, it became an instant classic, spawning dozens of spinoffs sung by major recording artists. However, unlike his antlered predecessor, Frosty’s rights didn’t remain with his individual creators. Today, the copyright in the song belongs to Warner Bros., while its title character, as conceived in the 1969 Rankin-Bass holiday special, is the property of Classic Media, a division of DreamWorks.

3. Santa Claus

Yes, even the head elf himself, jolly old Saint Nick, around whom the Christmases of millions of good girls and boys ages 3 to 10 revolve, can trace his origins back to the world of marketing. Well, sort of.

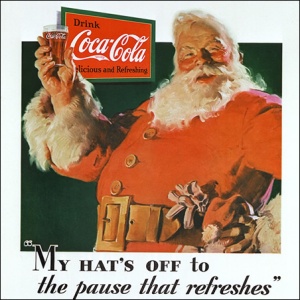

While there’s much debate about how big a part Coca-Cola actually played in giving Santa his modern-era makeover (plush red suit, black boots, and tousled white whiskers), there’s no doubt Coke deserves at least partial credit for updating him for the 1900s.

The famous 1931 Haddon Sundblom-painted version of Santa Claus (pictured above), the first in a long-running series of paintings done for Coke’s annual holiday campaign, is widely considered the first unofficial sighting of the Santa we know today—a corpulent, jovial Claus inspried by the rosy-cheeked elven character described in the 1823 poem, “The Night Before Christmas.” (If you’re interested in learning more about Coke’s influence on Santa’s evolution, I suggest this short video.) But even if you’re not quite prepared to declare Coke the winner of the create-a-Claus contest, it’s not so far-fetched that the soft drink company could, if they chose to, assert a degree of control over his commercial use.

To be clear, Coke can’t “own” Santa Claus any more than it can own Mother Goose, the Bogeyman, vampires or the Tooth Fairy. For one thing, unlike Rudolph and Frosty, Santa’s a mythical figure of unsettled origin, with no known “author” to speak of. For another, he’s loosely based on the legend of an actual person: a fourth-century Christian Saint who hailed from modern day Greece.

St. Nicholas, a.k.a. Santa Claus, has come a long way since the time of this 12th century fresco.

But what Coke can do is control the reproduction of the Sundblom series of images themselves, which span over four decades and number in the hundreds. Even those who argue that Sundblom’s version of Santa wasn’t the first of its kind—that depictions of a barrel-chested gift-giver dressed in red and white already existed—cannot deny Sundblom’s unique contributions to the character. His cheery, ruddy-faced, avuncular take on Santa not only gave his work classic Americana appeal, but imbued it with a level of artistic originality solidly deserving copyright protection.

The problem is that, with so many permutations of Sundblom-inspired Santas proliferating in the years since his work first appeared, a would-be infringer would almost have to do a direct lift of an original Sundblom before it could be considered a copy, let alone an illicit one. Anything short of a literal, willful reproduction would present a tall task for any 21st century IP attorney trying to argue misappropriation of Coke’s Santa.

But copyright isn’t the only right that Coke could assert over Santa. Another way the company could, theoretically, choose to control his use, is through trademark law. From 1931 to 1964, and in countless adaptations since, Sundblom’s Santa has been continuously used in connection with the Coca-Cola brand during the holidays. This could be prima facie evidence that Coke established a common law trademark in the character, due to the likely accumulation of secondary meaning during that time. In other words, Santa might have become a de facto Coke trademark, through no direct effort of the company itself, because he’s became so closely associated with its products in the minds of consumers. At least, that would be the argument.

But Santa’s part of our collective heritage, a cultural phenomenon who represents so much more to people than simply a bottle of soda, you say? Well, that may be true, but in trademark law, context is king. And the fact is that when Santa is pictured kicking back on Christmas Eve with a refreshing beverage in his hand, that image has been the near-exclusive province of Coca-Cola for more than eighty years.

Leprechauns, like Santa Claus, represent many things to many people—luck, good fortune etc.—but when a particularly pugnacious one is emblazoned next to the logo of the University of Notre Dame, it represents only one thing: the university’s storied athletics programs. Likewise, people identify the mythological winged horse Pegasus with positive things like strength, grace and beauty. But a great deal of them also associate it with the petroleum products of a particular oil and gas company. No one would argue that Exxon Mobil doesn’t have a legitimate right in its iconic Pegasus trademark, or that the fighting Irishman isn’t the exclusive property of the golden domers. A hypothetical Coke argument would sound in the same logic.

But common law trademark protection extends only so far. While it gives a company an exclusive right to use a word, name or symbol to identify it as the source of a certain good or service, it’s permitted to prevent others from doing the same only to the extent that’s required to prevent consumer confusion. So if Santa were declared a common law trademark tomorrow, Coke could likely prevent other beverage companies from using his image and likeness to sell carbonated soft drinks. But they couldn’t prevent anyone from using him to sell computers, flat-screen TVs, or luxury cars. So the scope of the right is actually quite limited.

This is all just theoretical postulating of course. In reality, the likelihood that Coke, one of the most American of all-American brands, would ever attempt to assert ownership over Santa Claus, even under the limited auspices of trying to prevent confusion, is slim to none. No brand, and especially not one as revered as Coke, would want to run the risk of being viewed as trying to exploit one of the most beloved children’s characters in human history. They’d be pilloried on social media faster than the man in red could make it down a single chimney, and publicly denounced as the Grinch that tried to steal Christmas.

So children, you can rest easy this Christmas Eve, nestled all snug in your beds, with visions of Haddon Sundblom’s Santa dancing in your heads. Oh, and in case you were wondering, that Grinch… he’s owned and licensed by Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P.

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year. See you in 2016.

The content of this blog is intended for informational purposes only. The information provided in this blog is not intended to and does not constitute legal advice, and your use of this blog does not create an attorney-client relationship between you and Brian J. Meli. Under the rules of certain jurisdictions, the material included in this blog may constitute attorney advertising. Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. Every case is different and the results obtained in your case may be different.

Loved it!

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

[…] The Rudolph Company, L.P. owns the copyright and trademark rights in Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. The song you hear every holiday season is copyrighted by St. Nicholas Music Inc., by the way, the […]

LikeLike

So, every story that uses Rudolph the reindeer is breaking the law?

LikeLike